(updated Sept 3, 2014)

“Did you bring to me sacrifices and offerings during the forty years in the wilderness, O house of Israel? You shall take up Sikkuth your king, and Kiyyun your star-god– your images that you made for yourselves, and I will send you into exile beyond Damascus,” says the LORD, whose name is the God of hosts. (Amos 5:25-27 ESV)

One of the difficulties in interpreting these verses in Amos is that the deities mentioned are obscure. Kiyyun is usually taken to be a Mesopotamian deity named Kaiwan which means “the steady one”, a name for Saturn. We know nothing about this deity except that the name appears in a list of Mesopotamian gods from a cuneiform text . Sikkut is usually thought to be Sakkuth, another obscure deity whose role in the pantheon was cupbearer to the gods. Sakkuth’s temple was in the city of Der, on the border of Elam – a long ways from Israel! (DDD – Dictionary of Deities and Demons) It may be that these obscure deities, Sakkuth and Kaiwan, are actually mentioned in this passage, but it is also possible that the MT is a little garbled here and that the LXX preserves a better reading,

Yea, ye took up the tabernacle of Moloch, and the star of your god Raephan, the images of them which ye made for yourselves. (Amo 5:26 LXE)

It is not difficult to reconcile the first clause of the LXX with the MT. With just a small change in vowel points, Sikkut becomes sukkat, which means a tent or dwelling. Likewise, malach can easily be repointed to read Molech – a deity often attested in the OT. So the LXX reading ‘tent of Molech’ seems better than the MT reading ‘Sikkuth your king’. The second phrase in the LXX reads ‘star of your god Raephan’. This is more difficult to reconcile with the MT. It is hard to say if the LXX is simply trying to smooth a difficult text or if it is preserving a more reliable Hebrew text. M. Pope notes that Ugaritic texts often speak of underworld spirits called the rephaim and the malku. They seem to be equivalent to the Annunaki in Mesopotamian texts. In Amos they appear together in the singular with the root letters MLK (Molech) and RPU (Raephan?). Pope argues that MLK and RPU were underworld deities that rose to receive the sacrifices offered to the dead during the marzea feast. (see below)

The naming of these two deities is further strengthened by the fact that Amos places the idolatrous worship of these deities in the context of Israel’s 40 years of wandering in the desert. He asks the rhetorical question, “Did you bring sacrifices and offerings during your 40 years in the wilderness?” (see note 2). In asking this question, Amos reminds Israel of the purity of their worship before reminding them of what happened next. “Yea, ye took up the tabernacle of Moloch, and the star of your god Raephan, the images of them which ye made for yourselves.” (Amo 5:26 LXE) The worship of these images is best understood in connection with the events that took place at Baal Peor as narrated in the book Numbers. In this case, Baal Peor is equivalent to the MLK and RPU.

Although the book of Numbers does not suggest that the deities worshiped at Baal Peor were connected to the underworld, a verse in the Psalms connects the worship at Baal-peor to sacrifices for the dead.

They joined themselves also unto Baal-peor, And ate the sacrifices of the dead. (Psa 106:28 ASV)

We can learn more about this feast from Ugaritc texts that link the rephaim to a funerary feast called the marzeah. According to M. Pope, the name of the feast is probably derived from the root word rzh which in Arabic means “to fall down from fatigue or other weakness and remain prostrate without the power to rise.” (Pope, M. H. and M. S. Smith (1994). Probative pontificating in Ugaritic and biblical literature : collected essays. Münster, Ugarit-Verlag) The goal of the marzeah feast was to get hammered.

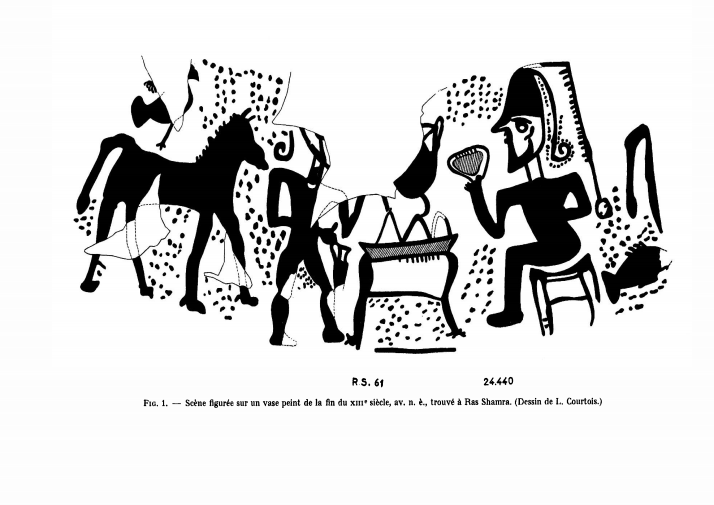

Probably the best known reference to the marzea feast comes from an Akkadian text found at Ras Shamra (13th BC) in which El gets so drunk he sees an apparition and ends up ‘wallowing in his excrement and vomit’. (Pope 1994, 155 ff). A cup found in the same room as the text illustrates the marzea.

Courtesy: Monsieur Claude F.-A.,Schaeffer Le culte d’El à Ras Shamra (Ugarit) et le veau d’or (supplément à la séance du 25 février), Persee

Another Akkadian text refers to an invitation to a marzea feast sent to the rephaim by the hero Danel after his son, Aqhat, is killed. (Pope 1994, 171).

The Bible also makes reference to the marzea. Jeremiah is forbidden to enter the ‘house of mourning’ (bet marzeach) because God had purposed to bring disaster on his people (Jer 16:5-9). Jeremiah is also commanded not to make a bald spot on his head or to cut himself – practices that were forbidden in Deut. 14:1. Thus it appears that the bet marzeah is associated with other forbidden forms of mourning for the dead. The prophet Amos also mentions a marzea feast but in this context, it clearly means ‘revelry’ and is associated with wine and music. Was it also associated with a feast for the dead? Amos doesn’t make this connection but it is possible that the meaning of marzea was originally confined to a funerary feast but was broadened to include all kinds of revelry.

The marzea feast also appears in later, non Biblical texts and inscriptions. For example, texts from Palmyra that date to the Hellenistic period make reference to a marzea feast held “at the houses of celebrated hetairai and served by beautiful girls as waitresses and musicians; the affair, understandably, often ended in sacrifices to Aphrodite Pandemos.” (Pope 1994, 170 citing Guhl and Koner, The Life of the Greeks and Romans) Interestingly enough, Rabbinic texts refer to the sacrifices offered to Peor as marzehim (Pope 1994, 169; Sifre Numbers 131) and also relate the idolatrous worship at Peor with the mayumas festivals that were “observed along the Mediterranean, especially in port cities like Alexandria, Gaza, Ashkelon and Antioch, with such licentiousness that Roman rulers felt constrained to ban them.” (Pope 1994, 169) It is noteworthy that these festivals were particularly associated with coastal cities on the eastern Mediteranean. Is it possible that the feast was transmitted to the Roman and Greek world through the Carthaginians? R. Good cites several Carthaginian stelae that make reference to the mayumas festival.

“for the mayumas of the people of Carthage”

Good suggests that the etymology of mayumas is found in the semitic terms: mai = water; yumas = carry, and thinks that this was a water carrying ceremony. This is probably the same ceremony described by Lucian writing in the 2nd century BC. Lucian describes a ceremony that was practiced at a Syrian temple called Hierapolis renown for the antiquity of the religious worship practiced there. He writes that twice a year (the solstices?) an image of gold, crowned by a golden pigeon is carried down to the sea. Water from the sea was brought back to the temple in Hierapolis. Furthermore, Lucian states that pilgrims from all around the world would carry sea water to the temple to pour it down a fissure in the rock in the floor of the temple to commemorate the receding of the Flood. Lucian thought that the temple at Hierapolis was dedicated to Atagartis (Syrian fertility goddess) but was built by Dionysus based on his eyewitness report that a “pair of phalli of great size are seen standing in the vestibule, bearing the inscription, “I, Dionysus, dedicated these phalli to Hera my stepmother.” (The Syrian Goddess http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/luc/tsg/tsg07.htm#fr_97)

The Athenian Festival of Anthesteria shares many similarities to the mayumas festival. It was a three day long festival that was foremost a drinking festival dedicated to Dionysius. During the feast, a sacred marriage was performed. The dead were believed to roam the streets during the three days of the festival. It might seem strange to have a sacred marriage connected to a funerary feast but these two elements are often connected in pagan ritual. John Garstang writes,

The conception of the Great Mother as goddess of the dead is by no means strained or unnatural, for the resurrection and future life is a dominant theme in the universal myth associated with her. And just as the dead year revived in springtime through her mediation, so she may have been entreated on behalf of the dead for their well-being or their return to life. (http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/luc/tsg/tsg04.htm)

The idolatrous worship at Baal Peor also combined sacrifices for the dead and fertility rituals. But can the Anthesteria, Mayumas or Marzeah festivals be related in any way to the idolatry at Peor? Apparently the makers of the Byzantine Madaba map thought so, for on the map they identify Baal-Peor as “Betomarseas alias Maioumas” (the house of Marzeah or Mayumas). (Pope 1994, 169) Thus the Byzantines connected the worship of Baal Peor with the Marzeah festival and the Mayumas festival. I think that is pretty amazing!

The Anthesteria was the precursor for All Souls that is still celebrated in Latin American countries in November.

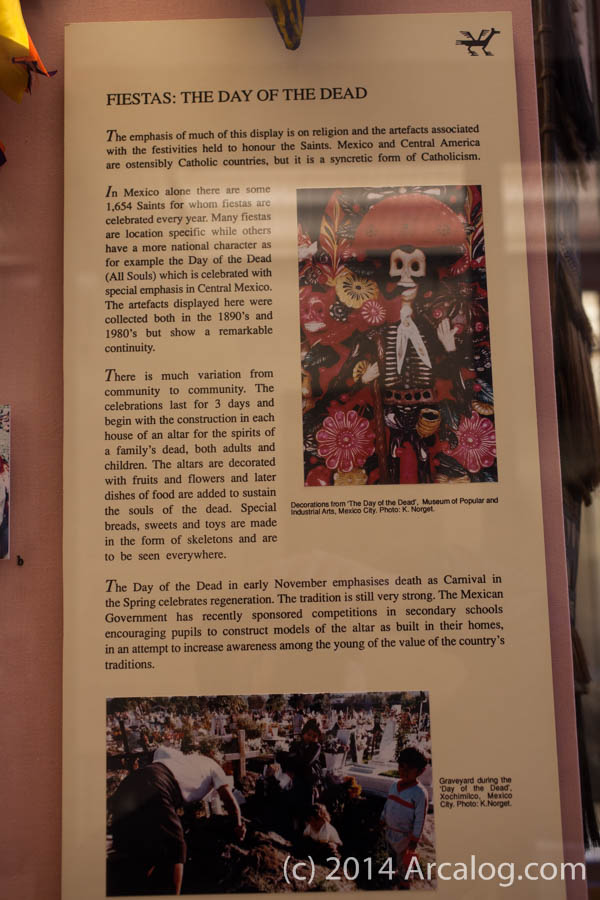

(MAA Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology – Cambridge)

A write up from the museum describes the Day of the Dead in this way:

Celebrations last for 3 days and begin with the construction in each house of an altar for the spirits of a family’s dead, both adults and children. The altars are decorated with fruits and flowers and later dishes of food are added to sustain the souls of the dead. Special breads, sweets and toys are made in the form of skeletons and are to be seen everywhere.” The Day of the Dead in early November emphasizes death as Carnival in the Spring celebrates regeneration. (MAA Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology – Cambridge)

Both the Anthesteria and All Souls have the dead as participants in the celebration.

Notes

(1) qubba (Num 25:8) – Phineas pursues an Israelite man and a Midianite woman into a ‘tent’ or ‘chamber’ and executes them. The sin here seems to be compounded in that the tent may have been a sacred shrine called a qubba and usually translated as tent. The word quBBâ is only found here. It is probably referring to a Midianite sacred shrine. According to Epiphanius the chief deity of the Arabs was Dhu l-Shara and had his chaabou in Petra. It is not clear from Epiphanius whether the temple in Petra was meant or the quadrangular black stone which represented Dhu l-Shara. Al-Bakri relates that the tribe of Bakr b. Wa’il together with the main body of the Iyad tribe had their centre of worship in Sindad in the region of Kufa and that their holy tent (bayt) there was called Dhat al-Ka’abat. A similar word is used to describe the most sacred Islamic shrine in Mecca – the kaaba – and also appears in an Arabic dedicatory inscription on a wall mosaic in the Dome of the Rock where the Dome of the Rock is referred to as a kubba – a word that apparently refers to a sacred shrine.

(2) One of the central tenets of Wellhausen’s documentary hypothesis was that the elaborate instructions for sacrifice are the invention of disenfranchised priests writing in the Exilic period. Wellhausen designates these late priestly texts ‘P’. He argues that in the pre exilic period, there was no well defined ritual for sacrifice but that the people offered sacrifices in the tradition of the Patriarchs. Amos 5:26 is used by Wellhausen to support his contention that sacrifice was not a central feature of Israelite ritual, which of course contradicts the Priestly documents in which sacrifice plays a central role. Wellhausen thinks that the obvious answer to Amos rhetorical question is ‘no’ – the Israelites did not offer sacrifices in the Desert. According to Wellhausen, they knew nothing of the Mosaic code. But the burden of proof falls to Wellhausen to explain why the Israelites would have ceased offering sacrifices in the desert. Sacrifices were offered continually in the Biblical text and in the ANE in general. The only reason one would not sacrifice is if one did not have meat. Perhaps such a condition did prevail at times during the sojourn of the Israelites in the wilderness but this has nothing to do with the date of Mosaic legislation.