As early as the Late Bronze Age, Egyptian traders called Carmel ‘the holy cape’ and a Greek traveller writing under the pseudonym of Scylax (6th century BC Greek geographer) referred to it as the “promontory of Zeus“. In the Greek pantheon, Zeus was a mountain and storm deity who dwelled on Mt. Olympus so it was natural for the Greeks to equate Zeus with the Semitic weather god Baal Shamem (Lord of the Heavens) who dwelled on Sapanu (Gk. – Mt Cassius; Heb. – Tsaphon).

The Roman historian Seutonias tells us that Vespasian traveled to Carmel to inquire of ‘the god of Carmel’ before taking up the siege of Jerusalem.

When he consulted the oracle of the god of Carmel in Judaea, the lots were highly encouraging, promising that whatever he planned or wished however great it might be, would come to pass…

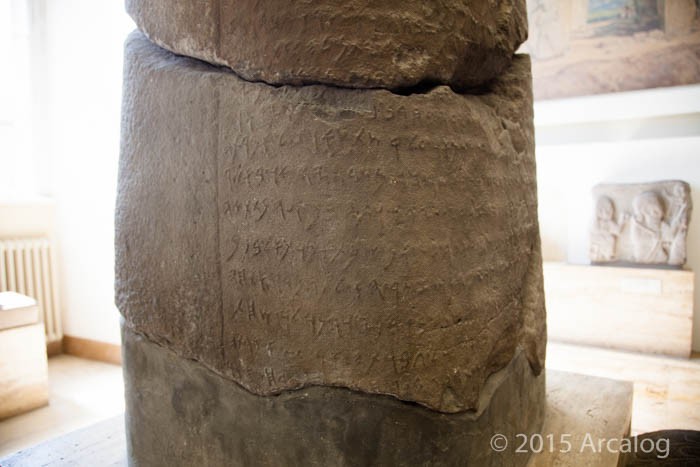

Tacitus also makes references to this event and tells us that there was no temple or statue on Carmel – just an altar. However, a statue must have been erected at a later date, the pedestal of which was discovered in an ancient monastery located on the top of Carmel. In the 1950’s M. Avi Yonah published a short article on the statue base discovered among a collection of antiquities belonging to the Carmelite monastery. The marble statue base dates to the 3rd century AD and would have stood twice life size.

The base of the statue contains the following inscription:

(Dedicated) to Heliopolitan Zeus (god of) Carmel (by) Gains lulius Eutychas colonist (of) Caesarea

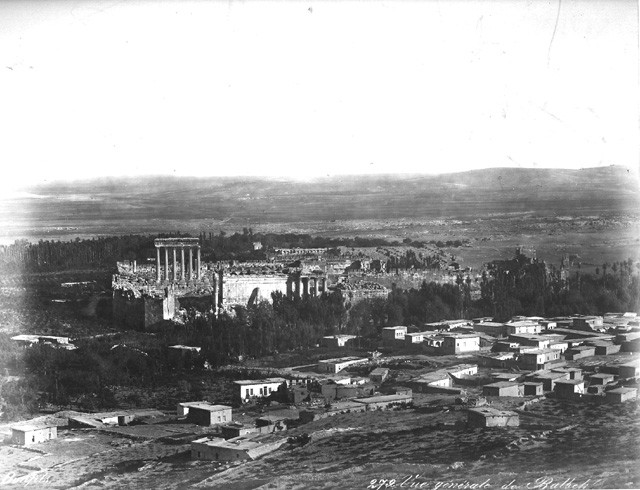

This inscription indicates that Baal, in his Greco-Roman form, the Heliopolitan Zeus, was worshipped on Carmel in the 3rd century AD. Jupiter was worshipped at Heliopolis (a city in Lebanon aka. Baalbek) alongside the Syrian fertility goddess Atargatis and their son, Mercury. Thus the Roman colonist who dedicated the statue to Baal of Heliopolis had adopted the god of the region. This was the usual practice for colonists.

The Bible makes frequent mention of the worship of Baal, although it is sometimes difficult to know when the word is used to refer to the deity and when it is used as a title meaning ‘lord’ or ‘master’. [1] When ‘baal’ appears in the names of Israelites or in their place names, it does not necessarily refer to a foreign deity – although it may! Baal was not listed among the foreign gods worshipped by Solomon, even though Ashtoreth (as Sidonian goddess) was. It would seem that only after Baal worship was made a state religion by king Ahab (under the influence of Jezebel, the daughter of the king of Sidon) was the word ‘baal’ consistently used with reference to a foreign deity and it was around this time that Judeans (and perhaps also most Israelites) stopped naming their children with the ephitet ‘baal’. In the time of Jeremiah, the word often appears in the plural as a generic reference to ‘foreign gods (baalim)’. At a later date, and only in a few cases, scribes changed the names of people in the Bible who had the theophoric element ‘baal’ in their names by replacing ‘baal’ with ‘boshet’ – which means ‘shame’. Thus Meriv-baal (Baal contends) became Mephiboshet (from the mouth of shame). This not so subtle emendation was a means of expressing disdain for the thing named. A similar phenomenon occurred when the Massoretes (9th-10th centuries AD) used the vowels from ‘boset’ (the Hebrew word for shame) and attached them to the names of pagan deities and cultic items. Some examples of the ‘boset vocalization’ are ‘Molech’, Ashtoreth’, and ‘Tophet’.

The confrontation between Elijah and the prophets of Baal on Carmel provides some information about the nature of Baal worship in Elijah’s day. Elijah taunts the prophets of Baal by asking them if perhaps their god was perhaps sleeping. This may be an allusion to Baal’s ‘death’ and subsequent journey to the underworld – an event connected with the disappearance of rain in the summer months.

In order to obtain a favourable answer from Baal, the priests cut themselves in a frenzy with swords and lances ‘as was their custom’. This custom is likewise referred to in a cuneiform tablet from Late Bronze Age Ugarit. According to the story recorded on this tablet, when the goddess Anat discovers that Baal, her brother / consort, was dead she began to cut herself in grief.

She [ploughed] her collar-bones,

she turned over like a garden her chest,

like a valley she ploughed her breast.

‘Baal is dead!

What has become of the Powerful One?

The Son of Dagan!

What has become of Tempest? (Wyatt, 2006)

The practice of cutting is also attested at Syrian temples in the Roman period. For example, Lucian of Samasota describes how the priests of Atargatis in Hierapolis would cut themselves during a religious festival. Lucian writes:

On certain days a multitude flocks into the temple, and the Galli in great numbers, sacred as they are, perform the ceremonies of the men and gash their arms and turn their backs to be lashed. Many bystanders play on the pipes the while many beat drums; others sing divine and sacred songs. (Lucian, De Dea Syria)

Lucian goes on to describe how spectators would sometimes lose control and join in the frenzied worship of the goddess by castrating themselves and then running wildly through the streets! This was the only way to become a priest (Galli) of the goddess.

Baal worship was just one aspect of a ‘fertility’ religion whose central tenet may be summarized in the Latin phrase do ut des – ‘I give so that you might give’. The goal of the sacrifice was to get something in return. Through proper ritual, the priests who officiated in the temple ensured fertility and prosperity of the land. The proper performance of the ritual was all important. [3] The degraded nature of Canaanite religion is seen in the fertility rituals that served also for the gratification of lust. The cult of the state and the fertility cult are both completely humanistic constructs. But that is the subject for another post.

Footnotes

[1] Likewise, Adon, which means ‘Lord’ was used as an epithet of YHWH. It also appears as the name of the Greek god Adonis, who was imported from Semites.

[2] Even today, in Papua New Guinea, a relative of the deceased will cut off a finger as a sign of mourning. More often, they will stage a show of intending to cut off the finger while their friends and family are expected hold them back.

[3] Plutarch writes,

It is usual with the Romans to recommence their sacrifices and processions and spectacles, not only upon such a cause as this [the disruption of a festival], but for any slighter reason. If but one of the horses which drew the chariots called Tensae, upon which the images of their gods were places, happened to fail and falter, or if the driver took hold of the reins with his left hand, they would decree that the whole operation should commence anew’ and, in later ages, one and the same sacrifice was performed thirty times over, because of the occurrence of some defect or mistake or accident in the service. Such was the Roman reverence and caution in religious matters. (Plutarch, Life of Coriolanus)

References

Avi-Yona, M. Mount Carmel and the God of Baalbek. Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2 (1952), pp. 118-124

Teixidor, Javier, The Pagan God: Popular Religion in the Greco-Roman Near East. Princeton, 1977

Wyatt, N. Religious Texts from Ugarit, Sheffield Academic Press, 2006