Child Sacrifice at the Tophet

The Hebrew University in Jerusalem

By: Andrew Cross

August 22, 2012

Introduction

For most of us living in the 21st century, the practice of child sacrifice is as shocking as it is difficult to comprehend. Apparently, it was also abhorrent to the prophet Jeremiah, for it was this sin in particular that Jeremiah condemned as he stood at the Potsherd Gate overlooking ‘Tophet’ and foretold Judah’s final destruction. The word ‘Tophet’ is derived from the Aramaic root ‘tpt‘ used to designate a ‘hearth’ or a framework set on the fire to support the victim. (note 62, Cogan 1970) The only other place in the Bible where this root appears outside of Jeremiah is in Is. 30:33 where it forms the word taphteh which means ‘funeral pyre’. [See 1 & 2 on the ‘boset vocalization’ and the location of the Valley of Ben Hinnom] Jeremiah addressed the ‘kings of Judah’ and the ‘inhabitants of Jerusalem’ who have ‘made strange this place’ by filling the ‘Valley of Ben Hinnom’ with the blood of innocents and by building ‘high places of Baal to burn their sons in the fire as burnt offerings to Baal.’ (Jer. 7:30-34; cf. Jer. 19:4-6)

These passages in Jeremiah raises a host of questions, not the least of which is, did the Judeans actually burn babies as burnt offerings to Baal in a valley near Jerusalem? And can this cult be connected to a fire cult to a Canaanite deity named Molech that is mentioned elsewhere in the Bible? Numerous Biblical and extra-Biblical sources claim that child sacrifice was common among the Phoenicians or their successors, the Carthaginians. The literary evidence is supplemented by evidence from archaeology. Thousands of jars containing the charred bones of infants and sacrificial animals have been excavated in ceremonial burial sites (called ‘tophets’ by their excavators) located near important Carthaginian cities. These sites were generally thought to be evidence of child sacrifice but over the last several decades an increasing number of scholars have expressed doubt that child sacrifice was ever a widespread practice among the Canaanites, Phoenicians, or Carthaginians. They argue that the numerous attributions of child sacrifice among the Carthaginians are nothing more than xenophobic Roman propaganda used to justify their war of extermination against Carthage (ie. Cato the Elder’s oft repeated phrase Carthago delenda est – Carthage must be destroyed!) These same scholars also doubt that the Bible can be used as a source of information on Canaanite religion. Biblical references to child sacrifice are explained as polemical attempts by late ‘redactors’ of the Bible to depict their opponents (apostate Judeans or Canaanites) as the unholy ‘other’. The children buried in the Carthagnian tophets were not sacrificed to the gods but died from natural causes and were given a special burial.

So was there ever a high place called ‘Tophet’ in the valley of Ben-Hinnom where children were sacrificed to a deity? To shed light on this question, we will begin by looking at the Biblical references to child sacrifice, particularly in Jeremiah. We will then proceed to look at the evidence for child sacrifice gathered from 1) contemporary inscriptions, 2) the testimony of late Roman, Jewish and Christian authors, and 3) archaeology. It is our position that a fire cult did exist in Jerusalem at the very end of the Judean monarchy in which children were sacrificed to a chthonic (underworld) deity.

The Tophet in Jeremiah

Jeremiah began his prophetic ministry in the 13th year of Josiah’s reign (629 BC). Jeremiah was still considered a youth at the time and Josiah was just beginning to take his first tentative steps towards reform. Five years later, in the 18th year of Josiah’s reign, the book of the Law was discovered in the temple which sparked more significant religious reforms. These reforms were accompanied by territorial expansion as Josiah took advantage of the power vacuum created by the disintegration of the Assyrian empire. The resurgence of Judean power ended with Josiah’s untimely death at the hand of Pharaoh Necho at Megiddo. The ascension to the throne of his son, Jehoicachin, saw the resumption of idolatrous worship. Battle lines were drawn between the assimilators who saw the rejection of foreign gods as the cause for Judah’s misfortune and those who sought national repentance and a return to the LORD. Foremost among the latter was the prophet Jeremiah.

It is impossible to determine when exactly Jeremiah delivered the oracle concerning Tophet in the Valley of Ben Hinnom. All we know is that Pashur was ‘the chief overseer of the temple which means the oracle was probably delivered sometime before 597 BC. This assumes that Pashur was taken into exile by the Babylonians in 597 BC, which is a reasonable assumption because a different overseer of the house is mentioned in Jeremiah 29:26. The oracle that Jeremiah delivered at the Tophet has an air of finality about it that suggests it was delivered on the eve of Jerusalem’s destruction.

Jeremiah was commanded by God to take a pot and break it outside of the Potsherd gate as a symbol of the destruction about to be visited upon Jerusalem and the towns of Judah. The significance of this act is better understood in the context of an earlier episode in which Jeremiah is told to visit the potter’s house and watch as the potter makes vessels from clay. The lesson of the potter is that as long as the clay is soft, it can be formed into another vessel according to the will of the potter. And if it is marred, the potter can remold it. But once the pot is dry, all that can be done is to throw it away. Jeremiah concludes his parable with a direct appeal to the people,

Thus says the LORD, Behold, I am shaping disaster against you and devising a plan against you. Return, every one from his evil way, and amend your ways and your deeds. Jer. 18:11b

But the people reject Jeremiah’s plea,

‘That is in vain! We will follow our own plans, and will every one act according to the stubbornness of his evil heart. Jer. 18:12b

To which Jeremiah responds,

‘Virgin Israel has done a very horrible thing.’ Do mountain streams run dry? Does the snow disappear from the peaks of Sirion? ‘But my people have forgotten me and makes offerings to false gods.’ (18:15)

Jeremiah leaves the potters house and gathers the elders of the priests and of the people to a location near the Potsherd gate. There he takes an earthenware flask (baqbuq) purchased from the potter and shatters it on the ground. This dramatic action was accompanied by an equally dire warning,

“Behold, I am bringing such disaster upon this place that the ears of everyone who hears of it will tingle.” Jer. 19:3b

The clay has become hard and can no longer be shaped according to the will of the potter. All that can be done is destroy the pot. The word for ‘tingle’ (tslal) is used elsewhere to describe the sound of clashing cymbals but here tslal refers to the sound of a shattering pot. The news of Jerusalem’s destruction will be as harsh on the ear as the sound a clashing cymbal or of a pot shattering. Jeremiah seems to be make a word play on the name of the earthen ware vessel (bakbuk) and the verb ‘make void’ (bakti). God will make void (bakti) the plans of the people and smash their cities like a pot (bakbuk). As we read these words, we can picture the prophet pouring out (bakti) the contents of his vessel on the ground as he declares, “I will make your plans void”, and then shattering the vessel to the ground with the final declaration, “so you too will be destroyed!”

[See Note 3 for a discussion on the various attempts to divide the Tophet passage into different units]

Jeremiah further states that the gods associated with this cult were unknown to them or their fathers. It is noteworthy in this regards that no hint of child sacrifice can be found in descriptions of the foreign cults introduced at the end of Solomon’s reign. Neither was human sacrifice among the list of crimes committed by Ahab despite his alliance with the royal house of Tyre. It is likely, therefore, that a cult involving child sacrifice only gained currency in Judah and Israel at a later date – perhaps as a result of Assyrian influence. Cogan notes that the age in which Manasseh ruled saw an “unprecedented abandonment of Israelite tradition.” (Cogan 1974, 114)

Child sacrifice was the primary practice associated with the Tophet (‘tophet’ = ‘hearth’) but Jeremiah may also allude to a burial ground that could have been a part of the ceremonial precinct at Tophet.

Men shall bury in Topheth because there will be no place else to bury. Thus will I do to this place, declares the LORD, and to its inhabitants, making this city like Topheth. (Jer 19:11 ESV)

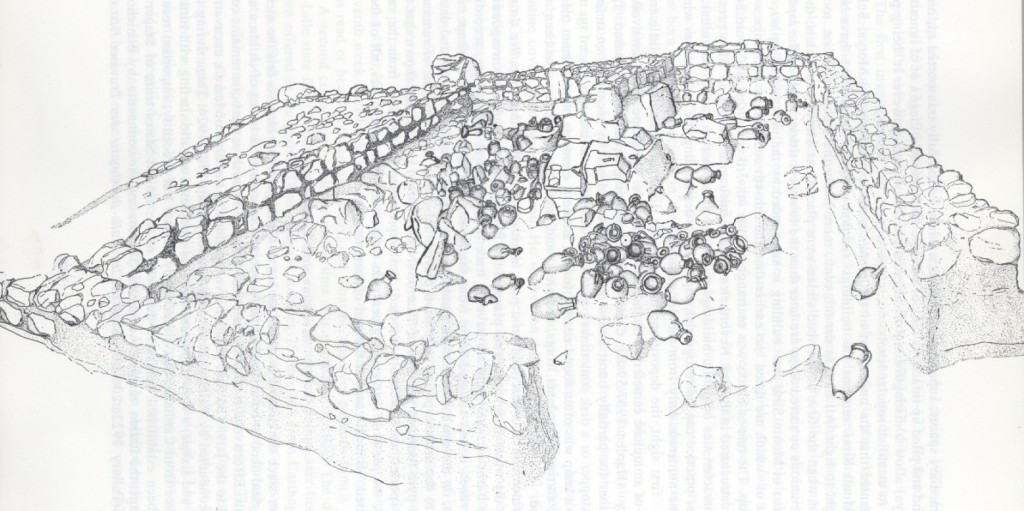

Jeremiah describes a situation in which Jerusalem will be so crowded with burials, that there will be no place left to bury. There could be some irony in his statement: All of Jerusalem will become like that crowded little graveyard at the Tophet… It is certainly possible that the Judeans practised rites similar to those of the Carthaginians and even had an infant burial place like the Carthaginian ones. [Fig 1]

The Carthaginian tophets are discussed in greater detail below. However, before we proceed to the archaeological evidence for child sacrifice, it will be helpful to compare the fire cult at Tophet with other instances of human sacrifice recorded in the Bible.

A Brief Survey of Biblical References to Child Sacrifice

Both sons and daughters were offered in the fire cult at Tophet. Likewise, sons and daughters are said to have been offered to Molech by the Canaanites. The prophet Ezekiel, on the other hand, only mentions the offering of sons. And only sons are mentioned in the context of the child sacrifice committed by the two apostatizing kings of Judah, Ahaz and Mannasseh, who are said to have passed their sons through the fire (lehiavir baesh – 2 Kings 16:3, 21:6); and in the context of Mesha, king of Moab, who offered his son up as a burnt offering (vayealeh ola – 2 Ki 3:27) on the wall of his besieged city causing the besiegers to return home. [3]

One of the abominable practices of the surrounding nations was the practice of passing a son or daughter through the fire. (Deut. 18:9-10; Lev. 18:21) The phrase ‘to burn’ (lishrof – Jer 7:31), ‘to pass through fire’ (lehiavir baesh – Lev. 18:21, 2 Ki. 23:10) and ‘to offer up a burnt offering’ (vayealeh ola – 2 Ki 3:27) seem to be used interchangeably.

The recipient of the sacrifice may be Molech, Baal, the Demons (shedim – Ps. 106:37; Deut. 32:17), or the recipient may go unspecified (Ezek. 20:31). Jeremiah makes no reference to Molech but rather connects the fire cult with Baal. Baal worship must have assumed many different forms. Indeed, in places, baal appears in the plural as a generic designation for the ‘gods’. It is safe to assume that the Baal worshipped at Tophet was essentially the same as Molech mentioned elsewhere in the context of child sacrifice.

This leads to another important question. What was nature of the god or demon named Molech?

Molech

It is not uncommon to read a commentary that treats Molech as an essentially fictional character invented by a post-exilic Judean ‘historian’ who felt it necessary to heap up the sins of the Canaanites and the Judeans in order to explain their downfall. These kinds of historiographical questions go beyond the scope of this paper but it begs the question, if a late Jewish historian invented Molech, did he also invent the Shepharvites and their obscure deities? For the Shepharvites also worshipped deities with names that incorporate the epithet ‘mlk‘ and whose rituals involved child sacrifice.

The Sepharvites burned their children in the fire to Adrammelech and Anammelech, the gods of Sepharvaim. 2 Kings 17:31

Kaufmann argues that Adrammelech and Anammelech contain elements that are ‘at home’ in the Phoenician and Ugaritic divine onomasticon: ‘adra‘- ‘mighty’ was a common epithet for Baal in Phoenicia; ‘ana‘ is a masculine form of Anat only known from Phoenician and Ugaritic names; and ‘mlk’ was a divine name used by the Phoenicians (ie. the Tyrian god Melquart – ‘god of the city’. Kaufman further suggests that the Sepharvites originated in Phoenicia instead of Aram. He notes that this location is consistent with the serial order of the locations given in II Kings 17:24 (Babylon, Cutha, Awwa(?), Hamath, Sepharvaim) and “with the generally agreed upon ascription of child sacrifice to the Canaanite culture.” (Kaufman 1978, note 9, pg. 102)

The CAD notes that malku in Akkadian is a common noun for a netherworld demon:

I gave (funerary) gifts to the Mal-ki, the Anunnaki, and all the gods dwelling in the netherworld. (TuL p 58 I 19)

When you [Shamash] appear the [nether-world] gods and the ma-al-[ku] rejoice. (this is parallel with – “the Igigi-gods rejoice”)

Why do you (witch) want to carry my soul to the ma-al-ki. [CAD – Vol. 10 pg 166-168 by way of a footnote in Tigay’s book, “You Shall Have No Other Gods”]

The Bible contains several references to the sacrifice of children to the ‘shedim’ – an Akkadian loan word that means ‘spirits of darkness’ (HALOT – Ps. 106:37; Deut. 32:17) If Molech was a cthonic deity then we are in a better position to understand why the Tophet was located in the valley of Ben Hinnom. Bailey notes that cults to gods of the underworld were built in valleys or by rivers thought to have sprung from the underworld. Altars to these underworld deities were sometimes “supplied with pipes so that the sacrificial blood could be channelled to the underworld deities who were thought to dwell just beneath them.” (Bailey 1986, 190) Cults to underworld deities were often connected with necromancy – the practice whereby the spirit of a deceased person is summoned from the underworld. (cf. 1 Sam 28:7 ff.) For example, Herodotus tells us that the river Acheron in Greece was thought to encircle the underworld before emerging aboveground and for this reason it was used for necromancy. (The Histories V 92 cf. Homer, Odyssey X 513) It is noteworthy in this regards that the fire cult of Molech almost always appears alongside necromancy in lists of forbidden Canaanite religious rites (Deut. 18:10-12; 2 Ki. 17:17; 2 Ki. 21:6). The only exception is in Leviticus where the fire cult of Molech is embedded in a list of illicit sexual relations (Lev. 18:11). [4]

A clear example of the connection between necromancy and Molech is found in the book of Isaiah where the prophet accuses the ‘children of the sorceress’ (57:3) with slaughtering children ‘in the valleys, under the clefts of the rock’ (57:5b). The children of the sorceress are said to make journeys ‘down even to Sheol’ with oil for a libation offering. They offer this libation to ‘the king’ (lmlk – 57:9). The reference to ‘the king’ (lmlk) is likely a reference to Molech especially since child sacrifice and a journey to the underworld are mentioned in the same context. Isaiah says that the children were sacrificed ‘in valleys, under the clefts of the rock’ which fits with what we know of the worship of cthonic deities.

R. Smith notes that, “human sacrifice is always offered on the wall or outside the city rather than at the altar to the god of the city.” (Smith 1972) For example, the sanctuaries of Juno Coelestis and Saturn “stood a little way outside the citadel or original city of Carthage on lower ground and at the beginning of the fourth century was surrounded by a thorny jungle”. (Smith 1972 – cf. also the temples discovered at Dougga which are also located outside of the city) Juno Coelestis and Saturn are the names of Roman deities that became assimilated to the Phoenician deities Tanit and Baal Hamon. As we will see, the worship of these Phoenician deities has been linked to child sacrifice. (See below)

To summarize, Molech was a ‘king’ of the underworld who was worshipped outside of cities, in valleys and clefts of the rocks (Is 57:5, 2 Kings 23:10), and whose worship was bound up with necromancy (Deut. 18:10-12; 2 Ki. 17:17; 2 Ki. 21:6).

Evidence for Child Sacrifice from Inscriptions and Icongraphy

Contemporary evidence from inscriptions shed further light on the practice of child sacrifice in the ANE. A 10th century stele set up by the Aramaean king Kapara in Gozan warns those who would violate the stele:

“May he burn seven of his sons before Adad.

May he release seven of his daughters to be cult prostitutes for Isthar.” (Cogan 1971)

Another Neo-Assyrian economic text also demands child sacrifice as the penalty for breaking a contract:

“He will burn his eldest son in the sacred precint of Adad.

He will burn his son to Sin.

He will burn his eldest daughter with 20 silas of cedar balsam to belet-seri.

He will burn either his eldest son or his eldest daughter with 2 homers of sweet-smelling spices to belet-seri. (Cogan 1971)

Cogan notes that these penalty clauses probably “could never have been actualized.” (Cogan 1971, 83) But they surely indicate that such sacrifices were not unknown.

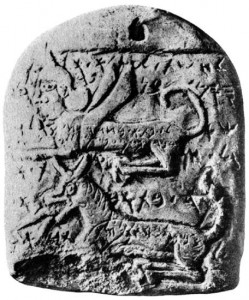

Iconographic evidence from amulets discovered in Arslan Tash, a city in upper Syria, depict a chthonic deity or a demon devouring children. (Brown 1991) The first amulet (Arslan Tash I) depicts “three demons or malevolent deities, two on the obverse and one on the reverse”. One of the beings on the obverse is swallowing a human – perhaps a child. Short incantations written in Phoenician with the Aramaic script (7th century) are inscribed on several of the creatures. On the sphinx it says:

To the female demon that flies in the dark chamber (say): Pass by, time and again, Lili(t)! (Brown 1991)

And on the she-wolf it says:

To the robbing, slaying female (say): Go away! (Brown 1991)

A similar kind of image is depicted on a grave monument discovered at Pozo Moro (6th century BC, Spain). In one scene, monsters sit down to a meal of ‘little people’. Whether they are children or not is difficult to determine but they are small in relation to the boar that is legs up on the offering table.

[envira-gallery id=”2610″]

The iconography and accompanying inscriptions on the Arslan Tash amulets and at Pozo Moro are admittedly difficult to interpret and may not have anything to do with child sacrifice. But they speak to the widespread belief in the ANE that misfortune was always due to the displeasure of the gods. Morganstern notes that, among the Babylonians, “sin, evil, sickness, possession by evil spirits, witchcraft, and misfortune, are all one and the same thing… something material, that has entered the body of the afflicted man. Consequently the curing of sickness, the expulsion of evil spirits, and the expiation of sin, are identical and must so be treated.” (Morganstern 2002) Morganstern goes on to state that sin was not originally conceived of as the ‘wronging of one’s neighbor’ or ‘violating laws of justice’ but was understood as a failure to fulfill ones religious duties. If a man suffered it was either because he “had neglected his sacrifice or had not offered it properly.” (Morganstern 2002) No doubt these generalizations can be extrapolated to other ancient cultures as well and may provide some rational for child sacrifice. When nature goes awry, the gods who must be appeased.

Evidence for Child Sacrifice from Greek and Roman Literature

Pausanius describes a yearly festival of Artemis and Dionysus at Patrae on the Greek mainland in which wreaths of corn were placed around the necks of children who then walked in a procession down to the Triklaria River and bathed. (Pausanius 7.20.1 as qtd. in Brown 1991) Upon emerging from the river, the children were given garlands of ivy to wear instead. This ceremony was said to have replaced an annual sacrifice of the fairest youth and maiden of Patrae to Artemis – a sacrifice made to bring an end to famine and disease that had come upon the people due to the desecration of Artemis’ sanctuary.

According to the history of Sanchuniathon (supposedly written in the 6th century BC but preserved by Eusebius in the 3rd century AD), Elos (Grk. Kronos), “during a great war, sacrificed his only son by ‘the nymph Anobret’, after dressing him in royal attire and preparing a special altar.” (Albright 1965, 234) Sanchuniathon also describes another myth in which Elos sacrifices his only son to his father Heaven (Uranus) in order to stop a destructive plague. (Albright 1965, 234) It is not difficult to see how these myths might have influenced people’s behavior, particularly in times of trouble.

This fact is highlighted by a story told by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus in an account of the siege of Carthage by Agathocles in 310 BC . According to Diodorus, the Carthaginians believed that the siege was the result failure to perform the proper sacrifices. Noble parents had purchased less worthy substitutes in secret rather than offer up their own children, . To make up for this, 200 noble children were chosen to be sacrificed and “placed in the bronze arms of a statue of Cronus.” (Libraries of History XX.14, qtd. in Brown, 1991)

While it is impossible check the accuracy of such stories, the persistence of child sacrifice among the Phoenicians is further substantiated by the fact that laws were written to outlaw the practice. The 3rd century A.D. historian Justin, in an epitome of the 1st century BC history of Pompeius Trogus, states that the Persian king Darius forbade the Carthaginians from offering human sacrifices… and from eating dog meat. (Justin, Epitoma Historiarum Phillippicarum XIX.1.10 – Brown 1991) Human sacrifice was again declared illegal in 87 BC by the Roman Senate. Despite this fact, the early church father Tertullian, who was born in Carthage, said that infants continued to be openly sacrificed to Saturn until the pro-consulate of Tiberius and that the practice continued in secret in Africa as late as the 2nd century A.D. Tertullian further states that priests were nailed to sacred trees for performing the cult. (Apology IX.2-4 – Brown 1991) Only in the third century AD was human sacrifice finally ended.

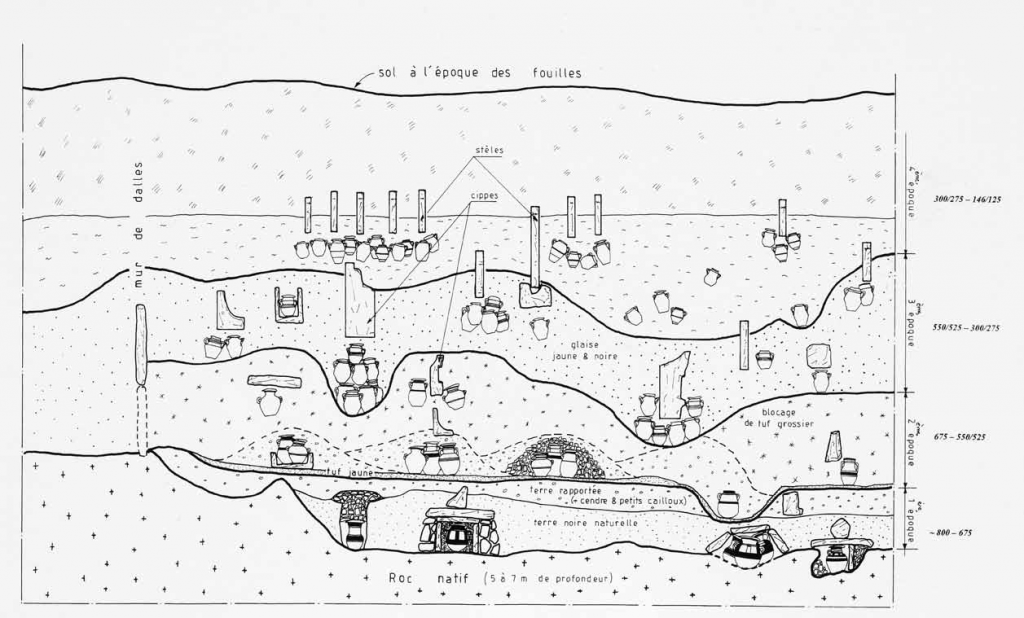

The Carthaginian Tophets

Recent attempts have been made by some scholars to salvage the reputation of the Carthaginians by arguing that they were the victims of Roman historians who sought to demonize their enemies. These scholars also argue that the Phoenicians, being inheritors of Canaanite culture, were singled out for attack by Christians and Jews for theological reasons. In recent years, the focus of the debate has centred on the discovery of mass infant burials (called ‘tophets’ by their original excavators based on the description of child sacrifice in Jeremiah) at nine locations in North Africa, Sicily and Sardinia – all of them former Phoenician colonies. Hundreds of clay urns containing the cremated remains of infants, often mixed with the bones of small animal and votive offerings, have been found in these burial sites. The fact that the remains were burned does not immediately indicate that this was a sacrificial offering. Incineration was more common than inhumation in Phoenicia from the 8th to the 6th centuries BC. (Gras, Rouillard, Teixidor 1991, 136)

The style of the stone stelae placed above the spot where the urn was buried changed over time. The first monuments were usually cubic or L-shaped sandstone cippi while taller, gabled limestone stelae began to appear in the late fifth century. Stager separates the history of the Tophet at Carthage into two major periods (Tanit I & II) that were further divided into eight phases.

• Phase 1 – burial pits were dug in the earth over bedrock and capped with stones (earlier excavator thought these were ‘cairns’) Sardinian urns from this period have geometric patterns that date to “no later than the eighth century B.C.” (Albright 1965, 238)

• Phases 2-3 – small, L-shaped cippi appeared over some urns

• Phases 4-6 – cubic cippi dominated

• Phases 7-8 gabled limestone stelae appeared along with cippi

A full sequence of urns were found ranging from 750 -700 BC to 146 BC. Tanit II is dated to 600-200 BC. Thus it seems that the tophets were used from the beginning of the establishment of the colony. Stager estimates that the Carthage Tophet eventually expanded to cover 54,000 to 64,000 sq ft and contained upwards of 20,000 urns. (Stager 1984) The Tophet cemetery was bordered by a temenous wall that prevented expansion. For this reason, the cemetery tended to get crowded with time. “Located in a space which could not expand indefinitely, the tophet must have presented an apparently chaotic aspect. One should not imagine a level area.” (Stager 1984) The archaeological evidence shows that occasionally the Tophet was levelled and new lay of soil brought in to create room for more burials.

[envira-gallery id=”2655″]

Shelby Brown has catalogued the religious motifs which commonly appear on the stelae. Her outline is followed here:

- The Caduceus – This symbol does not antedate the introduction of limestone stelae into Carthage. (circa 400 BC) The symbol appears as a shaft with a finial shaped like the number eight and resembles the staff carried by the Greek god Hermes (Hermes = Mercury) who conducted the dead to the underworld in Greek myth. Mercury was worshipped at Heliopolis and Hiearpolis. A caduceus was depicted on coins from Hierapolis, flanked by Zeus and Atagartis. Its appearance on the Carthaginian stelae may perhaps be connected to rites and rituals related to Baal as a god who dies and is resurrected again – cf. Dionysian and Orphic rituals.

- Uplifted Hand(s) – This symbol appears early on the limestone stelae. Gods and mortals raising their right hands in greeting is a common motif in ANE iconography. It may be comparable to the ‘Ear’ motif which has been interpreted as a symbol of the listening god. Yadin suggests that these uplifted hands are a symbol of Tanit. (see below)

- Crescent-disk – This is also an early symbol. Gsell interprets it as a lunar crescent superimposed on a full moon – a phenomenon sometimes visible several days after the new moon. (Brown 1991) The crescent disk symbol has also been found roughly incised on a L-shaped stele (TT 91.S1) at Tyre together with the inscription, “the client of Hammon.” Sader dates it on paleographic grounds to the 8th-7th centuries. (Sader 1991, 111)

- Sheep – The appearance of sheep may indicate the substitution of a sheep for an infant or sacrifice of a sheep together with an infant.

- Bottle – The bottle is found on cippi but never on thin-bodied stelae from later periods. The bottles share certain common features: a flat base, rounded shoulders, and a short vertical neck. The bottle is sometimes given eyes and a nose. It may be an anthropomorphic baetyl or idol that shares similarities with the ‘flat idols’ and the ‘violin idols’ from the Neolithic Aegean. (Brown 1991) It may also represent swaddled infants. (Brown 1991)

- Tanit symbol – This symbol appears in the form of a highly stylized woman that combines the simple geometrical elements of a circle, a triangle and a strait crossbar. The Tanit symbol is often shown together with ritual objects such as the caduceus, pitchers, small incense burners or containers for incense. Tanit is sometimes depicted holding a branch or a stalk of wheat, and a leaf that might indicate a connection with the 4th century cult of Kore and Demeter. Various attempts have been made to interpret the symbol. Gsell thought that the head was an astral symbol noting that it is sometimes shown separated from the body; the arms, depicted as a horizontal bar, represents the surface of an altar, and the triangle forms the body of the altar. Hours-Miedan also identifies the head as an astral disk but thinks the triangle is a sacred stone or baetyl and the cross bar divides the celestial from the chthonic element. Hours-Miedan suggests that the Tanit motif only gradually took on an anthropomorphic appearance. C. Picard compares the Tanit symbol to the Cretan figurines of the 2nd millennium BC of the Great Mother in which the triangle was a fertility symbol. Garbini thought the symbol represents an Egyptian ankh, a symbol of life, and the triangle, a symbol of fecundity. (Brown 1991) One of the earliest examples of the Tanit symbol is found on a stelae at Tyre. It combines the usual elements of a circle and crossbar but the triangle is replaced with a vertical line (Figure 3). This symbol looks very similar to the ankh symbol. It is often shown in the hands of the Egyptian goddess Neith; a mother goddess who is associated with the underground waters and with weaving and is often depicted with a weavers shuttle on her head. Here cult flourished at Sais during the 26th dynasty. Artemis and Athena also assumed attributes like that of Neith and were specifically associated with spinning and weaving. It is likely that a goddess with similar attributes was worshipped in the Jerusalem temple. Josiah put an end to her worship but it was apparently resumed in Ezekiel’s day.

And he broke down the houses of the male cult prostitutes who were in the house of the LORD, where the women wove hangings for the Asherah. (2Ki 23:7 ESV)

mlk is found in construct form with several other terms on Carthaginian funerary stele. These are listed here:

- mulk immor – Found on Phoenician stelae from Carthage Malta and Cirta dating to the seventh or sixth century. A Latin inscription on a stelae found at Ngaus in eastern Algeria dating to the 2nd or 3rd century transcribes mlk ‘mr as molchomor.

To the holy lord Saturn (Baal-hammon), a great sacrifice of night-time (sacrum magnum nocturnum), molchomor, breath for breath, blood for blood, life for life. (Albright 1965, 235)

According to this inscription, the sacrifice to Baal-hammon was made at night. This confirms the chthonic nature of this sacrifice. The phrase ‘breath for breath, life for life, blood for blood, indicates that the sacrificed animal took the place of the child. In other places, mulk immor is sometimes followed by the Phoenician phrase: bsr(m) btm. A 1st century Latin transcription of this phrase – de sua pecunia – has been variously interpreted as “paid with his own funds” (favoured by Vida) or “paid in full” (favoured by Albright). Albright alternatively suggests that the Hebrew translation should read “(whose) body is intact.” (Albright 1965, 236) - mulk adam – This construct may indicate either that the sacrifice was made ‘by a man’ or ‘of a man’. The latter translation is favored by P. Mosca and R. de Vaux. (Brown 1991) Albright suggests that the interchange of the terms of mlk’mr with mlk‘dm may indicate “an increasing tendency to substitute a lamb for a child, a fact which would explain the substitutionary formula ‘life for life,’ etc.” (Albright 1965, 236) However, upon further excavation of the tophet at Carthage, the opposite has proven to be true. Stager claims that the percentage of animal bones to children’s bones actually decreases over time indicating that, if anything, child sacrifice became more prevalent and not less. [6] This may be due to the devastating wars with Rome that made Carthage’s situation desparate.

- mulk baal – May refer to the sacrifice of humans or animals. It appears on stelae of all periods from Carthage, early stelae from Motya and Sulcis, and on two late stelae from Sousse. It probably refers to the dedication of the sacrifice to that deity.

The question naturally arises whether there is a connection between ‘mlk’ on votive stelae and ‘lmlk’ (to Molech) found in Lev. 18:21 and elsewhere. Eissfeld put forward the theory that ‘mlk’ was always used as a technical term for sacrifice in both the Bible andon Carthaginian contexts. Albright, expanding further on Eissfeld’s thesis, stated, “Punic molk and Heb. Molech (vocalized correctly by MT) are in fact the same word, and both refer to a sacrifice which was, for Phoenicians and Hebrews alike, the most awe-inspiring of all possible sacred acts-whether it was considered as holy or as an abomination….” (Albright 1965, 236) Albright goes on to state that, “There are probably few competent scholars who now believe that a god Moloch is intended in any biblical passage referring to human sacrifice. ” (Albright 1965, 236) Hays, writing more recently, acknowledges the influence of Eissfeld’s theory that ‘moloch’ refers to a sacrifice and not to a god but states that this theory “is no longer in favor.” (Hays, 2011, 180) It would seem that scholarship has come full circle on this question. The best alternative is presented by Heider who agrees with Eissfeldt that “in the Phoenician and Punic contexts mlk is indeed a type of sacrifice, but it is one that has grown out of an ancient cult of the god Molek which can be traced back to the Ebla material of the third millennium.” (Brown 1991, 15) The fact that gods of the Sepharvaim both contain the mlk element supports this later interpretation.

Albright argues that due to the relatively late date ascribed to the custom of setting up commemorative stelae in connection with tophet sacrifices, it is improbable that the practice “was derived from Phoenicia proper.” (Albright 1965, 238) However early stelae have been discovered in a cemetery near Tyre. Unfortunately, due to the political situation in Lebanon, most of the stelae were sold into private collections on the black market. Several dozen stelae were rescued by researchers at the American University of Beirut and their inscriptions published. The stelae were discovered together with cinerary urns and vessels for libations, suggesting the existence of a tophet on Tyre. Unfortunately, the contents of the cinerary urns were emptied soon after ‘excavation’ by the grave robbers. However, some of the cinerary urns rescued by the American University of Beirut still contained some fragments of bone that could be identified as human although the poor preservation of the contents of the urn make it impossible to determine the age. According to Conheeny and Pipe, “their size was not consistent with them being the remains of small infants.” (Conheeny and Pipe 1991, 85) However, they note that their conclusions are “quite tentative” due to “the poor nature of the material.” (Conheeny and Pipe 1991, 85)

Based on the epigraphy of the Phoenician inscriptions, the stelae should be dated from the 9th to the 6th centuries. (Sader 1991, 109) The divine names Tanit, Melquart, Baal, Ashtart, Hammon, El, and Eshmun are all attested. (Sader 1991, 109) The discovery of the name Tanit on one of these stele is important evidence that the cult to this goddess did not originate in North Africa during the Carthiginian period but rather has its origins in Phoenicia.

Yadin provides further compelling evidence that the worship of Baal Hammon and Tannit has a Phoenician origin. Yadin notes that, apart from the Punic stelae, Baal Hammon appears in an inscription in only one other place – on an orthostat dating to the late 9th century BC discovered at Zinjirli. A crescent disc nearly identical to those found on Punic stelae is inscribed on this same stele. Yadin makes a convincing case for identifying Baal Hammon with the moon god Baal Harran who he believes was introduced into the pantheon of Samal under Assyrian influence. (Yadin 1970, 211)

[envira-gallery id=”2628″]

The discovery of a crescent-disc symbol together with two upraised arms in the context of a LBIII temple at Hazor provides an intriguing link between Carthaginian and Cannanite iconography. The statute of a seated male deity with a lunar crescent incised on his chest was found nearby as was a silver standard etched with the symbol of a crescent-disk and the figure of a woman holding two snakes. Y. Yadin interprets the crescent-disc as Baal-Hammon and the woman as Tanat, his consort. Rather than see the two uplifted hands as a symbol of devotion – he interprets them as a symbol of Tanat. Yadin further suggests that one of the epithets of Tanit, ‘the face of Baal’, may be reflected in the use of masks attached to the face of the statue. This might account for the crude workmanship on the face of the seated god. (Yadin 1972, 73) Masks are also commonly found in Punic contexts – many of them too small to be worn by humans. Based on these discoveries at Hazor and their similarity to later Punic religious motifs, Yadin concludes that, “Several aspects of Canaanite worship found their continuation at least from the Late Bronze Age till the end of the Punic period.” (Yadin 1972, 217)

Conclusion

The tangle of gods and their iconography is exceptionally difficult to unravel. That being said, there is a significant body of evidence that leads us to believe that child sacrifice was prevalent among certain cultures and at certain times in the ANE. This evidence comes in the form of dedicatory inscriptions to Baal Hammon and Tanit placed above the cremated remains of infants in the Carthaginian ‘tophets’. It comes by way of the Phoenician myths that have the god Elos offering his son to his father Uranus. The overwhelming testimony of Greek, Roman, Jewish, and Christian writers point to the prevalence of child sacrifice among the the Carthaginians. And perhaps most convincingly, we have the words of the prophet Jeremiah who condemned the practice of child sacrifice in his day. It is fair to assume – although perhaps an oversimplification – that the worship of Baal at the Tophet condemned by Jeremiah was in some way related to the worship of Baal Hammon by the Phoenicians and the worship of Molech mentioned elsewhere in the Bible. The practice of child sacrifice seems to have been adopted by the Judeans during the reign of Ahaz and to have become prevalent during the reign of Manasseh.

It is admittedly difficult for us to get our minds around the idea that it was once considered necessary or beneficial to offer one’s own child as a burnt offering to a god / demon. But before we reject such a possibility outright, it is worth considering another awful historical fact. Primo Levi, in his book ‘The Drowned and the Saved’, recalls the taunt of cynical SS militiamen who reminded the prisoners that history would surely explain away the awful reality of the crematoriums: “There will perhaps be suspicions, discussions, research by historians, but there will be no certainties, because we will destroy the evidence together with you. And even if some proof should remain and some of you survive, people will say that the events you describe are too monstrous to be believed: they will say that they are the exaggerations of Allied propaganda and will believe us, who will deny everything, and not you. We will be the ones to dictate the history of the Lagers.” (Levi 1988, 1) To explain away such uncomfortable historical realities is to allow the ideas and beliefs that gave rise to them to bear fruit once again.

Footnotes

[1] Tophet is pronounced with the ‘boset vocalization’, boset being the Hebrew word for ‘shame’. By attaching the vowels ‘o’ and ‘e’ to a word, scribes expressed their disgust at the thing signified. Other examples of the ‘boset’ vocalization are ‘Molech’ and ‘Astoreth’ – the names of Canaanite deities.

[2] Although located in a valley, Jeremiah refers to ‘high places’ at the Tophet. bamot is derived from the Akkadian word ‘bamtu’ which means ‘ridge’. It is usually translated as ‘high place’ although it came to be associated more generally with a cultic place and for this reason could be located in a valley. There has been some discussion as to which valley should be identified with the Valley of Hinnom. Most scholars today identify it with ‘Wadi er-Rababi’, which runs in a southerly direction along the western side of Jerusalem before turning eastward along the southern edge of Jerusalem. However, Hugo Gressman suggests that the valley may be Wadi an-Nar south of the junction between the Western valley (today identified as Hinnom) and the Kidron. (Holladay 1986, 268) The Arabic name for this valley means “the Valley of Hell.” The only geographical information that Jeremiah provides is that Tophet was in some way associated with the Potsherd gate. The location of the Potsherd gate is unknown but the name of the gate indicates that it was a place where garbage was dumped outside of the city . This hypothesis is further supported by the Jerusalem Targum which identifies the Potsherd Gate with the Dung Gate. Unfortunately, the location of this gate is also unknown.

[3] Some commentators have suggested that that the condemnation of child sacrifice in Jeremiah 19 is a late addition to an earlier, simpler, narrative in which Jeremiah condemned the people for social injustice. For example, Bracke suggests that the phrase – ‘they have filled this place with the blood of the innocent’ (v. 4b) was not a reference to child sacrifice but was an “accusation of social injustice of an unspecified nature”. (Bracke 2000) Similarly, Carroll suggests that the original theme of Jeremiah was not the condemnation of cultic practices but the refusal to hear Yahweh’s words. He singles out certain recurring phrases as evidence of a late redaction; ie. – “the ears of everyone who hears of it will tingle” (19:3b) is found in a similar form in 1 Sam 3:11 and 2 Kings 21:12; passages that Carroll also attributes to a late redactor. Carroll highlights other phrases found in Jeremiah that he believes belong to a late redaction: “because they have stiffened their neck” (Jer. 7.25, 19:15; 25:3-4, 25. 3-4; 26:5, 35:14-15; 44:4); and “food for the birds and beasts” cf. 7:33, 16:4, 34:20; Deut 28:26. (Carroll 1986)

However, there are problems with dividing this section of prose in order to account for a Deuteronomic influence:

- The wordplay between bakbuk and bakti is lost. (Holladay 1986)

- Language that is attributed to Dtr could just as well have preceded the prophet and been used by him to connect his message with earlier warnings.

- There are no compelling internal textual reasons to divide this narrative. To separate the Tophet material from an earlier account of the breaking of the earthenware flask at the Potsherd gate renders the entire account meaningless in as much as the Potsherd Gate is linked geographically with Tophet in the narrative.

If a cult did exist in Hinnom “involving scandalous pagan rites… then it is all together likely that Jeremiah would refer to the offensive practices perpetrated there.” (Thompson 1980)

[4] Further evidence of child sacrifice among the Moabites may be found in Amos 2:1. The Massoretic text reads, “because he burned the bones of the king of Edom into lime’. However, this phrase does not seem to make any sense. H. Tur Sinai offers a different interpretation. By repointing the text, the phrase ‘melek Edom lassid’ can be read ‘molek adam lassed’ which is translated,

Because of three offences of Moab, Because of four, I shall surely requite him! Because he burns the bones of a human sacrifice to a demon.” (Albright 1965, 240 – see below for more on ‘mulch adam’)

One weakness with this translation is that bones were not burned as part of a sacrifice whereas they were burned to make lime or whitewash. Perhaps this has more to do with the desecration of a tomb.

[5] In his discussion of the bamot, Albright argues that the ‘bamot’ were places devoted to ancestor worship similar to the Greek hero-shrines. If he is correct, then this further supports the connection between the ‘bamot’ and necromancy. (Hays 2011, 138)

[6] Stager has shown that the ratio of children to animal bones increased over time. In the 7th to 6th century 30% of the bones in his sample (Group A – 80 urns) were animal whereas by the 4th century only 10% of the bones in his sample (Group B – 50 urns) were animal. It was also found that among the urns from group A, newborns buried singly predominated whereas in group B, 68% of the urns were single and the rest were multiple burials. Of those urns that contained multiple burials, older children aged one to three years old were buried alongside those of a new born or premature.

References

Aaron, B. (2002). “From the Hills of Adonis through the Pillars of Hercules: Recent Advances in the Archaeology of Canaan and Phoenicia.” Near Eastern Archaeology 65(1): 69-80.

Albenda, P. (2005). “The “Queen of the Night” Plaque: A Revisit.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 125(2): 171-190.

Bailey, L. R. (1986). “Enigmatic Bible Passages: Gehenna: The Topography of Hell.” The Biblical Archaeologist 49(3): 187-191.

Bracke, J. M. (2000). Jeremiah 1-29. Louisville, Ky., Westminister John Knox Press.

Brown, S. S. (1991). Late Carthaginian child sacrifice and sacrificial monuments in their Mediterranean context. Sheffield, England, Published by JSOT Press for the American Schools of Oriental Research.

Carroll, R. P. (1986). Jeremiah : a commentary. Philadelphia, Westminster Press.

Clifford, R. J. (1990). “Phoenician Religion.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research(279): 55-64.

Cogan, M. (1974). Imperialism and religion : Assyria, Judah, and Israel in the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E. Missoula, Mont., Society of Biblical Literature : distributed by Scholars Press.

Gras, M. R., Peirre; Teixidor, Javier (1991). “The Phoenicians and Death.” Berytus 39.

Hahn, S. W. and J. S. Bergsma (2004). “What Laws Were “Not Good”? A Canonical Approach to the Theological Problem of Ezekiel 20:25-26.” Journal of Biblical Literature 123(2): 201-218.

Hays, C. B. (2011). Death in the Iron Age II and in First Isaiah. Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck.

Holladay, W. L. and P. D. Hanson (1986). Jeremiah 1 : a commentary on the Book of the Prophet Jeremiah, chapters 1-25. Philadelphia, Fortress Press.

Macurdy, Grace Harriet (1912). The Origin of a Herodotean Tale in Connection with the Cult of the Spinning Goddess Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association Vol. 43, pp. 73-80

Mettinger, T. N. D. (1994). “[untitled].” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research(293): 84-87.

Morgenstern, J. (2002). The Doctrine of Sin in the Babylonian Religion. San Diego, Book Tree.

Morton, S. (1975). “A Note on Burning Babies.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 95(3): 477-479.

O’Ceallaigh, G. C. (1962). “And So David Did to All the Cities of Ammon.” Vetus Testamentum 12(2): 179-189.

Patai, R. (1965). “The Goddess Asherah.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 24(1/2): 37-52.

Quinn, J. (2011) “The Cultures of the Tophet: Identification and Identity in the Phoenician Diaspora” Cultural Identity and the Peoples of the Ancient Mediterranean

Sader, H. (1991). “Stela at Tyre.” Berytus 39.

Shelby, B. (1992). “Perspectives on Phoenician Art.” The Biblical Archaeologist 55(1): 6-24.

Smith, W. R. (1972). The religion of the Semites; the fundamental institutions. New York,, Schocken Books.

Snaith, N. H. (1966). “The Cult of Molech.” Vetus Testamentum 16(1): 123-124.

Stager, L. E. a. S. R. W. (1984). “Child Sacrifice at Carthage – Religious Rite or Population Control?” Biblical Archaeological Review 10(1).

Thompson, J. A. (1980). The book of Jeremiah. Grand Rapids, Eerdmans.

Vance, D. R. (1994). “Literary Sources for the History of Palestine and Syria: The Phœnician Inscriptions.” The Biblical Archaeologist 57(2): 110-120.

Wyatt, N. (2002). Religious texts from Ugarit. London ; New York, Sheffield Academic Press.

Yadin, Y. (1970). Symbols of Deities at Zinjirli, Carthage, and Hazor, University Microfilms.

Yadin, Y. (1972). Hazor: with a chapter on Israelite Megiddo. London, New York,, Oxford University Press for the British Academy.

Thank you for sharing this effectual exposition on Tophet and its historical roots pertaining to child sacrifice. I appreciate the intensive labor that would entail such a concise overview. I am a Christian and a real believer in the accuracy and eternal record of The Holy Bible. Please, if you journal and share with others, similar writing that demonstrates evidence of ancient canaanite practices–in particular ancient Jericho, I would be grateful to also be included in your reader audience.